COLLECTIVE VARIABLES MODULE

Reference manual for NAMD

Code version: 2024-06-04

Updated versions of this manual: [GROMACS] [LAMMPS] [NAMD] [Tinker-HP] [VMD]

Alejandro Bernardin, Haochuan Chen, Jeffrey R. Comer, Giacomo Fiorin, Haohao Fu, Jérôme

Hénin, Axel Kohlmeyer, Fabrizio Marinelli, Hubert Santuz, Joshua V. Vermaas, Andrew D.

White

Contents

2 Writing a Colvars configuration: a crash course

3 Enabling and controlling the Colvars module in NAMD

3.1 Units in the Colvars module

3.2 NAMD parameters

3.3 Using the scripting interface to control the Colvars module

3.3.1 Setting up the Colvars module

3.3.2 Using the Colvars version in scripts

3.3.3 Loading and saving the Colvars state and other information

3.3.4 Accessing atomic data

3.3.5 Managing collective variables

3.3.6 Applying and analyzing forces on collective variables

3.3.7 Managing collective variable biases

3.3.8 Loading and saving the state of individual biases

3.4 Configuration syntax used by the Colvars module

3.5 Global keywords

3.6 Input state file

3.6.1 Restarting in NAMD.

3.6.2 Changing configuration upon restarting.

3.7 Output files

3.8 File formats

3.8.1 Configuration and state files.

3.8.2 Index (NDX) files

3.8.3 XYZ coordinate files

3.8.4 PDB coordinate files

3.8.5 Grid files: multicolumn text format

3.8.6 Output trajectory files

4 Defining collective variables

4.1 Choosing a function

4.2 Treatment of periodic boundary conditions

4.3 Distances

4.3.1 distance: center-of-mass distance between two groups.

4.3.2 distanceZ: projection of a distance vector on an axis.

4.3.3 distanceXY: modulus of the projection of a distance vector on a plane.

4.3.4 distanceVec: distance vector between two groups.

4.3.5 distanceDir: distance unit vector between two groups.

4.3.6 distanceInv: mean distance between two groups of atoms.

4.4 Angles

4.4.1 angle: angle between three groups.

4.4.2 dipoleAngle: angle between two groups and dipole of a third group.

4.4.3 dihedral: torsional angle between four groups.

4.4.4 polarTheta: polar angle in spherical coordinates.

4.4.5 polarPhi: azimuthal angle in spherical coordinates.

4.5 Contacts

4.5.1 coordNum: coordination number between two groups.

4.5.2 selfCoordNum: coordination number between atoms within a group.

4.5.3 hBond: hydrogen bond between two atoms.

4.6 Collective metrics

4.6.1 rmsd: root mean square displacement (RMSD) from reference positions.

4.6.2 Advanced usage of the rmsd component.

4.6.3 eigenvector: projection of the atomic coordinates on a vector.

4.6.4 gyration: radius of gyration of a group of atoms.

4.6.5 inertia: total moment of inertia of a group of atoms.

4.6.6 dipoleMagnitude: dipole magnitude of a group of atoms.

4.6.7 inertiaZ: total moment of inertia of a group of atoms around a chosen axis.

4.7 Rotations

4.7.1 orientation: orientation from reference coordinates.

4.7.2 orientationAngle: angle of rotation from reference coordinates.

4.7.3 orientationProj: cosine of the angle of rotation from reference coordinates.

4.7.4 spinAngle: angle of rotation around a given axis.

4.7.5 tilt: cosine of the rotation orthogonal to a given axis.

4.7.6 eulerPhi: Roll angle from references coordinates.

4.7.7 eulerTheta: Pitch angle from references coordinates.

4.7.8 eulerPsi: Yaw angle from references coordinates.

4.8 Protein structure descriptors

4.8.1 alpha: -helix content of a protein segment.

4.8.2 dihedralPC: protein dihedral principal component

4.9 Raw data: building blocks for custom functions

4.9.1 cartesian: vector of atomic Cartesian coordinates.

4.9.2 distancePairs: set of pairwise distances between two groups.

4.10 Geometric path collective variables

4.10.1 gspath: progress along a path defined in atomic Cartesian coordinate space.

4.10.2 gzpath: distance from a path defined in atomic Cartesian coordinate space.

4.10.3 linearCombination: Helper CV to define a linear combination of other CVs

4.10.4 customColvar: Helper CV to define a mathematical expression as CV from other CVs

4.10.5 gspathCV: progress along a path defined in CV space.

4.10.6 gzpathCV: distance from a path defined in CV space.

4.11 Arithmetic path collective variables

4.11.1 aspathCV: progress along a path defined in CV space.

4.11.2 azpathCV: distance from a path defined in CV space.

4.11.3 Path collective variables in Cartesian coordinates

4.11.4 aspath: progress along a path defined in atomic Cartesian coordinate space.

4.11.5 azpath: distance from a path defined in atomic Cartesian coordinate space.

4.12 Dense neural network in CV space (MLCV)

4.13 Volumetric map-based variables

4.13.1 mapTotal: total value of a volumetric map

4.13.2 Multiple volumetric maps collective variables

4.14 Shared keywords for all components

4.15 Periodic components

4.16 Non-scalar components

4.16.1 Calculating total forces

4.17 Linear and polynomial combinations of components

4.18 Custom functions

4.19 Scripted functions

4.20 Defining grid parameters for a colvar

4.21 Trajectory output

4.22 Extended Lagrangian

4.23 Multiple time-step variables

4.24 Backward-compatibility

4.25 Statistical analysis

5 Selecting atoms

5.1 Atom selection keywords

5.2 Moving frame of reference.

5.3 Treatment of periodic boundary conditions.

5.4 Performance of a Colvars calculation based on group size.

6 Biasing and analysis methods

6.1 Thermodynamic integration

6.2 Adaptive Biasing Force

6.2.1 ABF requirements on collective variables

6.2.2 Parameters for ABF

6.2.3 Multiple-walker ABF

Output files of multiple-walker ABF.

6.2.4 Output files

6.2.5 Multidimensional free energy surfaces

6.3 Extended-system Adaptive Biasing Force (eABF)

6.3.1 CZAR estimator of the free energy

6.3.2 Zheng/Yang estimator of the free energy

6.4 Adiabatic Bias Molecular Dynamics (ABMD)

6.5 Metadynamics

6.5.1 Treatment of the PMF boundaries

6.5.2 Required metadynamics keywords

6.5.3 Output files

6.5.4 Performance optimization

6.5.5 Ensemble-Biased Metadynamics

6.5.6 Well-tempered metadynamics

6.5.7 Multiple-walker metadynamics

6.6 Harmonic restraints

6.6.1 Moving restraints: steered molecular dynamics

6.6.2 Moving restraints: umbrella sampling

6.6.3 Changing force constant

6.7 Computing the work of a changing restraint

6.8 Harmonic wall restraints

6.9 Linear restraints

6.10 Adaptive Linear Bias/Experiment Directed Simulation

6.11 Multidimensional histograms

6.11.1 Defining grids for multidimensional histograms

6.11.2 Output options for multi-dimensional histograms

6.11.3 Histogramming vector variables

6.12 Reweighted free-energy landscapes from accelerated MD

6.13 Probability distribution-restraints

6.14 Defining scripted biases

6.15 Performance of scripted biases

7 Tcl command-line interface: list of commands

7.1 Commands to manage the Colvars module

7.2 Commands to manage individual collective variables

7.3 Commands to manage individual biases

8 Syntax changes from older versions

9 Compilation notes

In molecular dynamics simulations, it is often useful to reduce the large number of degrees of freedom of a physical system into few parameters whose statistical distributions can be analyzed individually, or used to define biasing potentials to alter the dynamics of the system in a controlled manner. These have been called ‘order parameters', ‘collective variables', ‘(surrogate) reaction coordinates', and many other terms.

Here we use primarily the term ‘collective variable', often shortened to colvar, to indicate any differentiable function of atomic Cartesian coordinates, , with between and , the total number of atoms:

| (1) |

This manual documents the collective variables module (Colvars), a software that provides an implementation for the functions with a focus on flexibility, robustness and high performance. The module is designed to perform multiple tasks concurrently during or after a simulation, the most common of which are:

- apply restraints or biasing potentials to multiple variables, tailored on the system by choosing from a wide set of basis functions, without limitations on their number or on the number of atoms involved; while this can in principle be done through a TclForces script, using the Colvars module is both easier and computationally more efficient;

- calculate potentials of mean force (PMFs) along any set of variables, using different enhanced sampling methods, such as Adaptive Biasing Force (ABF), metadynamics, steered MD and umbrella sampling; variants of these methods that make use of an ensemble of replicas are supported as well;

- calculate statistical properties of the variables, such as running averages and standard deviations, correlation functions of pairs of variables, and multidimensional histograms: this can be done either at run-time without the need to save very large trajectory files, or after a simulation has been completed (post-processing).

Detailed explanations of the design of the Colvars module are provided in reference [1]. Please cite this reference whenever publishing work that makes use of this module, alongside any other publications for specific features being, according to the usage summary printed when running a Colvars-enabled MD simulation or analysis.

The Colvars configuration is a plain text file or string that defines collective variables, biases, and general parameters of the Colvars module. It is passed to the module using back-end-specific commands documented in section 3.

Example: steering two groups of atoms away from each other. Now let us look at a complete, non-trivial configuration. Suppose that we want to run a steered MD experiment where a small molecule is pulled away from a protein binding site. In Colvars terms, this is done by applying a moving restraint to the distance between the two objects. The configuration will contain two blocks, one defining the distance variable (see section 4 and 4.3.1), and the other the moving harmonic restraint (6.6).

colvar {

name dist

distance {

group1 { atomNumbersRange 42-55 }

group2 { indexGroup C-alpha_15-30 }

}

}

harmonic {

colvars dist

forceConstant 20.0

centers 4.0 # initial distance

targetCenters 15.0 # final distance

targetNumSteps 500000

}

Reading this input in plain English: the variable here named dist consists in a distance function between the centers of two groups: the ligand (atoms 42 to 55) and the -carbon atoms of residues 15 to 30 in the protein (segment name PR). To the “dist" variable, we apply a harmonic potential of force constant 20 kcal/mol/Å, initially centered around a value of 4 Å, which will increase to 15 Å over 500,000 simulation steps.

The atom selection keywords are detailed in section 5.

Example: using multiple variables and multiple biasing/analysis methods together. A more complex example configuration is included below, showing how a variable may be constructed by combining multiple existing functions, and how multiple variables or multiple biases may be used concurrently. The colvar indicated below as “" is defined as the difference between two distances (see 4.3): the first distance () is taken between the center of mass of atoms 1 and 2 and that of atoms 3 to 5, the second () between atom 7 and the center of mass of atoms 8 to 10 (see 5). The difference is obtained by multiplying the two by a coefficient or , respectively (see 4.17). The colvar called “" is the coordination number calculated between atoms 1 to 10 and atoms 11 to 20. A harmonic restraint (see 6.6) is applied to both and : to allow using the same force constant , both and are scaled by their respective fluctuation widths and . A third colvar “alpha" is defined as the -helical content of residues 1 to 10 (see 4.8.1). The values of “" and “alpha" are also recorded throughout the simulation as a joint 2-dimensional histogram (see 6.11).

colvar {

# difference of two distances

name d

width 0.2 # estimated fluctuation width

distance {

componentCoeff 1.0

group1 { atomNumbers 1 2 }

group2 { atomNumbers 3 4 5 }

}

distance {

componentCoeff -1.0

group1 { atomNumbers 7 }

group2 { atomNumbers 8 9 10 }

}

}

colvar {

name c

coordNum {

cutoff 6.0

group1 { atomNumbersRange 1-10 }

group2 { atomNumbersRange 11-20 }

tolerance 1.0e-6

pairListFrequency 1000

}

}

colvar {

name alpha

alpha {

psfSegID PROT

residueRange 1-10

}

}

harmonic {

colvars d c

centers 3.0 4.0

forceConstant 5.0

}

histogram {

colvars c alpha

}

Here, we document the syntax of the commands and parameters used to set up and use the Colvars module in NAMD [2]. One of these parameters is the configuration file or the configuration text for the module itself, whose syntax is described in 3.4 and in the following sections.

The “internal units" of the Colvars module are the units in which values are expressed in the configuration file, and in which collective variable values, energies, etc. are expressed in the output and colvars trajectory files. Generally the Colvars module uses internally the same units as its back-end MD engine, with the exception of VMD, where different unit sets are supported to allow for easy setup, visualization and analysis of Colvars simulations performed with any simulation engine.

Note that angles are expressed in degrees, and derived quantities such as force constants are based on degrees as well. Some colvar components have default values, expressed in Ångström (Å) in this documentation. They are converted to the current length unit, if different from Å. Atomic coordinates read from XYZ files (and PDB files where applicable) are expected to be expressed in Ångström, no matter what unit system is in use by the back-end (NAMD) or the Colvars Module. They are converted internally to the current length unit as needed. Note that force constants in harmonic and harmonicWalls biases (6.6) are rescaled according to the width parameter of colvars, so that they are formally in energy units, although if width is given its default value of 1.0, force constants are effectively expressed in kcal/mol/(colvar unit).

To avoid errors due to reading configuration files written in a different unit system, it can be specified within the input:

- units — Unit system to be used

string, context: global

A string defining the units to be used internally by Colvars. In NAMD the only supported value is NAMD's native units: real (Å, kcal/mol).

To enable a Colvars-based calculation, the colvars on command must be added to the NAMD script. Two optional commands, colvarsConfig and colvarsInput can be used to define the module's configuration or continue a previous simulation. Because these are static parameters, it is typically more convenient to use the cv command in the rest of the NAMD script.

- colvars — Enable the Colvars module

Default: off boolean, context: NAMD configuration file

If this flag is on, the Colvars module within NAMD is enabled. - colvarsConfig — Configuration file for the collective variables

UNIX filename, context: NAMD configuration file

Name of the Colvars configuration file (3.4, 3.5 and following sections). This file can also be provided by the Tcl command cv configfile. Alternatively, the contents of the file (as opposed to the file itself) can be given as a string argument to the command cv config. - colvarsInput — Input state file for the collective variables

UNIX filename, context: NAMD configuration file

Keyword used to specify the input state file's name (3.6). If the input file is meant to be loaded within a Tcl script section, the cv load command may be used instead.

After the first initialization of the Colvars module, the internal state of Colvars objects may be queried or modified in a NAMD script:

cv method arg1 arg2 ...

where method is the name of a specific procedure and arg1, arg2, …are its required and/or optional arguments.

In the remainder of this section, the most frequently used commands of the Colvars scripting interface

are discussed and exemplified. For a full list of scripting commands available, see section 7.

If the NAMD configuration parameter colvars is on, the cv Tcl command can be used anywhere in the NAMD script, and will be invoked as soon as NAMD begins processing Tcl commands.

To define new collective variables and/or biases for immediate use in the current session, configuration can be loaded from an external configuration file:

cv configfile "colvars-file.in"

This can in principle be called at any time, if only flags internal to Colvars are being modified. In practice, when new atoms or any new atomic properties (e.g. total forces) are being requested, initialization steps will be required that are not carried out during a simulation. Therefore, it is generally good practice in a simulation to change the Colvars configuration outside the scope between segments of the same computation.

To load the configuration directly from a string the “config" method may be used:

cv config "keyword { ... }"

This method is particularly useful to dynamically define the Colvars configuration within a NAMD script. For example, when running an ensemble of umbrella sampling simulations in NAMD, it may be convenient to use an identical script and define the specific window through environment variables.

In the following example, the environment variable “SLURM_ARRAY_TASK_ID" is set in a Slurm array job to increasing values starting at 0. The value of this variable is used to define the window's numeric index, and the umbrella restraint center beginning at 2.00 for the first window, and increasing in increments of 0.25 for all other windows:

cv configfile colvar-definition.in

set window $env(SLURM_ARRAY_TASK_ID)

cv config "harmonic {

name us_${window}

colvars xi

centers [expr 2.0 + 0.25 * ${window}]

...

}"

The vast majority of the syntax in Colvars is backward-compatible, adding keywords when new features are introduced. However, when using multiple versions simultaneously it may be useful to test within the script whether the version is recent enough to support the desired feature. The “version" can be used to get the Colvars version for this use:

if { [cv version] >= "2020-02-25" } {

cv config "(use a recent feature)"

}

After a configuration is fully defined, the “load" method may be used to load a state file from a previous simulation that contains e.g. data from history-dependent biases), to either continue that simulation or analyze its results:

cv load "oldjob.colvars.state"

or more simply using the prefix of the state file itself:

cv load "oldjob"

The latter version is particularly convenient in combination with the NAMD reinitatoms command, for

example:

reinitatoms oldjob

cv load oldjob

The step number contained by the loaded file will be used internally by Colvars to control time-dependent biases, unless firstTimestep is issued, in which case that value will be used.

When the system's topology is changed during simulation via the structure command (e.g. in constant-pH simulations), it is generally best to reset and re-initialize the module from scratch before loading the corresponding snapshot:

structure newsystem.psf

reinitatoms snapshot

cv reset

cv configfile new_config

cv load snapshot

The “save" method, analogous to “load", allows to save all restart information to a state file. This is normally not required during a simulation if colvarsRestartFrequency is defined (either directly or indirectly by the NAMD restart frequency). Because not only a state file (used to continue simulations) but also other data files (used to analyze the trajectory) are written, it is generally recommended to call the save method using a prefix, rather than a complete file name:

cv save "job"

For computational efficiency the Colvars module keeps internal copies of the numeric IDs, masses, charges, positions, and optionally total forces of the atoms requested for a Colvars computation. At each simulation step, up-to-date versions of these properties are copied from the central memory of NAMD into the internal memory of the Colvars module. In a post-processing workflow or outside a simulation (e.g. when using VMD), this copy can be carried out as part of the update method:

cv update

which also performs the (re-)computation of all variables and biases defined in Colvars.

For example, the current sequence of numeric IDs of the atoms processed by Colvars can be obtained as:

cv getatomids

and their current positions as:

cv getatompositions

This may prove useful to test the correctness of the coordinates passed to Colvars, particularly in regard to periodic boundary conditions (5.3). There is currently no mechanism to modify the above fields via the scripting interface, but such capability will be added in the future.

A special case are collective variables that are based on centers of mass, or volumetric maps (see e.g. mapTotal). These are often computed by NAMD itself, and any atoms that are used only for such variables will not be included in the lists above.

While running a simulation, or when setting one up in VMD, it is possible to examine all the forces that were last applied by Colvars to the atoms, or are about to be applied:

cv getatomappliedforces

where the length and order of this sequence matches that provided by the getatomids method. A simpler way of testing the stability of a Colvars configuration before or during a simulation makes use of aggregated data, such as the energy:

cv getenergy

the root-mean-square of the Colvars applied forces:

cv getatomappliedforcesrms

or the maximum norm of the applied forces:

cv getatomappliedforcesmax

which can be matched to a specific atom via its numeric ID obtained as:

cv getatomappliedforcesmaxid

See 7.1 for a complete list of scripting commands used to manage atomic data and runtime parameters of the Colvars module.

After one or more collective variables are defined, they can be accessed with the following syntax.

cv colvar "name" method arg1 arg2 ...

where “name" is the name of the variable.

For example, to recompute the collective variable “xi" after a change in its parameters, the following command can be used:

cv colvar "xi" update

This ordinarily is not needed during a simulation run, where all variables are recomputed at every step (along with biasing forces acting on them). However, when analyzing an existing trajectory, e.g. in VMD, a call to update is generally required.

While in all typical cases all configuration of the variables is done with the “config" or “configfile" methods, a limited set of changes can be enacted at runtime using:

cv colvar "name" modifycvcs arg1 arg2 ...

where each argument is a string passed to the function or functions that are used to compute the variable, and are called colvar components, or CVCs (4.1). For example, a variable “DeltaZ" made of a single “distanceZ" component can be made periodic with a period equal to the unit cell dimension along the -axis:

cv colvar "DeltaZ" modifycvcs "period ${Lz}"

Please note that this option is currently limited to changing the values of the polynomial superposition parameters componentCoeff, or of the componentExp to update on the fly, of period, wrapAround or forceNoPBC options for components where it is relevant.

If the variable is computed using many components, it is possible to selectively turn some of them on or off:

cv colvar "name" cvcflags flags

where “flags" is a list of 0/1 values, one per component. This is useful for example when script-based path collective variables in Cartesian coordinates (4.11.3) are used, to minimize computational cost by disabling the computation of terms that are very close to zero.

Important: None of the changes enacted by the “modifycvcs" or “cvcflags" methods will be saved to state files, and will be lost when restarting a simulation, deleting the corresponding collective variable, or resetting the module with the “reset" method.

As soon as a colvar “xi" and its associated biasing potentials are up to date (i.e. during a MD run, or after the respective “update" methods have been called), the force applied onto the colvar is known and may be accessed through the getappliedforce method:

cv colvar "xi" getappliedforce

See also the use of the outputAppliedForce option to have this force be saved to file during a simulation.

Aside from the biasing methods already implemented within Colvars (6) this force may be incremented ad hoc, for example as part of a custom restraint implemented by scriptedColvarForces:

cv colvar "xi" addforce force

where “force" is a scalar or a vector (depending on the type of variable “xi"). If addforce is used during a simulation step, the force added by will be communicated to the corresponding atoms as soon as Colvars communicates all forces to NAMD.

For certain types of variable, the force applied directly on a colvar may be combined with those acting indirectly on it via the interatomic force field, making up the total force. When the outputTotalForce keyword is enabled, or when a biasing method that makes explicit use of the total force is enabled, the total force may be obtained as:

cv colvar "xi" gettotalforce

Note that not all types of variable support total-force computation, and the value of the total force may not be available immediately within the same simulation step: see the documentation of outputTotalForce for more details.

See 7.2 for a complete list of scripting commands used to manage collective variables.

Because biases depend only upon data internal to the Colvars module (i.e. they do not need atomic coordinates from NAMD), it is generally easy to create them or update their configuration at any time. For example, given the most current value of the variable “xi", an already-defined harmonic restraint on it named “h_xi" can be updated as:

cv bias "h_xi" update

During a running simulation this step is not needed, because an automatic update of each bias is already carried out.

Another circumstance when “update" may be called e.g. as part of the function invoked by scriptedColvarForces, it is executed before any biasing forces are applied to the variables, thus allowing to modify them. This use of “update" is often used e.g. in the definition of custom bias-exchange algorithms as part of the NAMD script. Because a restraint is a relatively light-weight object, the easiest way to change the configuration of an existing bias is deleting it and re-creating it:

# Delete the restraint "harmonic_xi"

cv bias harmonic_xi delete

# Re-define it, but using an updated restraint center

cv config "harmonic {

name harmonic_xi

centers ${new_center}

...

}"

# Now update it (based on the current value of "xi")

cv bias harmonic_xi update

It is also possible to make the change subject to a condition on the energy of the new bias:

...

cv bias harmonic_xi update

if { [cv bias harmonic_xi energy] < ${E_accept} } {

...

}

Some types of bias are history-dependent, and the magnitude of their forces depends not only on the values of their corresponding variables, but also on previous simulation history. It is thus useful to load information from a state file that contains information specifically for one bias only, for example:

cv bias "metadynamics1" load "old.colvars.state"

or alternatively, using the prefix of the file instead of its full name:

cv bias "metadynamics1" load "old"

A corresponding “save" function is also available:

cv bias "metadynamics1" save "new"

Please note that the file above must contain only the state information for that particular bias: loading a state file for the whole module is not allowed.

This pair of functions is also used internally by Colvars to implement e.g. multiple-walker metadynamics (6.5.7), but they can be called from a scripted function to implement alternative coupling schemes.

See 7.3 for a complete list of scripting commands used to manage biases.

Configuration for the Colvars module is passed using an external file, or inlined as a string in a NAMD script using the Tcl command cv config "...". Configuration lines follow the format “keyword value" or “keyword { ... }", where the keyword and its value must be separated by one or more space characters. The following formatting rules apply:

- Keywords are case-insensitive; for example, upperBoundary is the same as upperboundary and UPPERBOUNDARY); note that their string values are however still case-sensitive (e.g. names of variables, file names).

- A long value, or a list of multiple values, can be distributed across multiple lines by using curly braces, “{" and “}": the opening brace “{" must occur on the same line as the keyword, following at least one space character; the closing brace “}" may be at any position after that; any keywords following the closing brace on the same line are not valid (they should appear instead on a different line).

- Many keywords are nested, and are only meaningful within the specific context of another keyword; for example, the keyword name is available inside the block of the keyword colvar {...}, but not outside of it; for every keyword documented in the following, the “parent" keyword that defines such context is also indicated.

- If a keyword requiring a boolean value (yes|on|true or no|off|false) is provided without an explicit value, it defaults to ‘yes|on|true'; for example, ‘outputAppliedForce' may be used as shorthand for ‘outputAppliedForce on'.

- The hash character “#" indicates a comment: all text in the same line following this character will be ignored.

- Outside of comments, only ASCII characters are allowed for defining keywords, and the only white-space characters supported are spaces, tabs and newlines: a warning will be printed upon detection of non-ASCII characters in a configuration line, which include both characters that are visibly “special", as well as those with a very similar appearance to ASCII ones (for instance, non-breaking spaces); common ways to identify/remove non-ASCII characters are using the Emacs text editor, or using LC_ALL=C vi.

- Tcl syntax is generally not available inside a Colvars configuration file/string, but it is possible to use Tcl variables or bracket expansion of commands when configuration is passed via the command cv config "..."; for example, this is particularly useful when combined with NAMD's parameter introspection, e.g. cv config "colvarsTrajFrequency [DCDFreq]" allows synchronizing the output frequencies of NAMD and Colvars trajectory files. .

The following keywords are available in the global context of the Colvars configuration, i.e. they are not nested inside other keywords:

- colvarsTrajFrequency — Colvar value trajectory frequency

Default: 100 positive integer, context: global

The values of each colvar (and of other related quantities, if requested) are written to the file outputName.colvars.traj every these many steps throughout the simulation. If the value is 0, such trajectory file is not written. For optimization the output is buffered, and synchronized with the disk only when the restart file is being written. - colvarsRestartFrequency — Colvar module restart frequency

Default: NAMD parameter restartFreq positive integer, context: global

When this value is non-zero, a state file suitable for restarting will be written every these many steps. Additionally, any other output files produced by Colvars are written as well (except the trajectory file, which is written every colvarsTrajFrequency steps). It is generally a good idea to leave this parameter at its default value, unless needed for special cases or to disable automatic writing of output files altogether. If neeed, writing of all output files can still be triggered at any time via the save scripting function. - indexFile — Index file for atom selection (GROMACS “ndx" format)

UNIX filename, context: global

This option reads an index file (usually with a .ndx extension) as produced by the make_ndx tool of GROMACS. This keyword may be repeated to load multiple index files. A group with the same name may appear multiple times, as long as it contains the same indices in identical order each time: an error is raised otherwise. The names of index groups contained in this file can then be used to define atom groups with the indexGroup keyword. Other supported methods to select atoms are described in 5. - smp — Whether SMP parallelism should be used

Default: on boolean, context: global

If this flag is enabled (default), SMP parallelism over threads will be used to compute variables and biases, provided that this is supported by the NAMD build in use. - sourceTclFile — Tcl file to be sourced at startup

UNIX filename, context: global

This option causes the provided Tcl script file to be loaded at startup, e.g. to initialize the Tcl callback procedures for scripted variables or biases.

Several of the sampling methods implemented in Colvars are time- or history-dependent, i.e. they work by accumulating data as a simulation progresses, and use these data to determine their biasing forces. If the simulation engine uses a checkpoint or restart file (as GROMACS and LAMMPS do), any data needed by Colvars are embedded into that file. Otherwise, a dedicated state file can be loaded into Colvars directly.

When a dedicated Colvars state file is used, it may be in either one of two formats:

- Formatted, i.e. “text" format, which takes more space and is slower to to load/save but is also portable across different platforms and even different simulation engines (save for changes in physical units). This format is used by default, unless explicitly requested otherwise.

- Unformatted, i.e. “binary" format, which is both space-efficient and quick to load/save, but requires that the same NAMD build was used to write the file and that the Colvars configuration remains the same. This format is supported by Colvars versions starting 2023-09-25. Colvars state files can be written in binary format by setting the environment variable “COLVARS_BINARY_RESTART" to 1.

In either format, the state file contains accumulated data as well as the step number at the end of the run. The step number read from a state file overrides any value that NAMD provides, and will be incremented if the simulation proceeds. This means that the step number used internally by Colvars may not always match the step number reported by NAMD. This is particularly inmportant in NAMD, which represents step numbers as a 32-bit integers that overflows after 2 billion steps, effectively negating the usefulness of the firstTimeStep keyword. However, step numbers are implemented correctly in the Colvars state file.

Before the Colvars module is initialized in NAMD, the colvarsInput keyword can be used to give the name of a state file. After initialization of the Colvars module, a state file may be loaded at any time with the Tcl command cv load. Both versions support loading Colvars state files in either format (binary or text).

In some cases, it is useful to modify the configuration of variables or biases between consecutive runs, for example by adding or removing a restraint. Some special provisions will happen in that case. When a state file is loaded, no information is available about any newly added variable or bias, which will thus remain uninitialized until the first compute step. Conversely, any information that the state file may contain about variables or biases that are no longer defined will be silently ignored. Please note that these checks are performed based only on the names of variables and biases: it is your responsibility to ensure that these names have consistent definitions between runs.

The flexibility just described carries some limitations: namely, it is only supported when reading text-format Colvars state files. Instead, restarting from binary files after a configuration change will trigger an error. It is also important to remind that when switching to a different build of NAMD, the binary format may change slightly, even if the release version is the same.

To work around the potential issues just described, a text-format Colvars state file should be loaded. This is the default in NAMD unless the “COLVARS_BINARY_RESTART" is set to 1, and this information is only provided here for troubleshooting purposes.

When the output prefix outputName is defined, the following output files are written during a simulation run:

- A state file, named outputName.colvars.state, which is written at the end of the specified run, and can also be written at any time with the scripting command save (3.3.3). This file is in plain text format by default, regardless of the value of binaryOutput of the NAMD coordinate and velocity files, or in binary format if the environment variable COLVARS_BINARY_RESTART is set to a non-zero integer. The state file can be used to continue a simulation: unless its contents are embedded in the checkpoint file of the MD engine itself (currently, GROMACS and LAMMPS support this), instructions for loading the Colvars state file will be required in the simulation script (see 3.6).

- If the parameter colvarsRestartFrequency is larger than zero and the restartName prefix is defined, a restart file is written every that many steps: this file is fully equivalent to the final state file. The name of this file is restartName.colvars.state.

- If the parameter colvarsTrajFrequency is greater than 0 (default value: 100 steps), a trajectory file, named outputName.colvars.traj, is written during the simulation. Unlike a state file, this file is not needed to restart a simulation, but can be used for post-processing and analysis. The format of this file is described in sec. 3.8.6.

- Additionally, certain features, when enabled, can emit output files with a specific purpose: for example, potentials of mean force (PMFs) can be written to file to be analyzed or plotted. These files are described in the respective sections, but as a general rule they all use names beginning with the outputName prefix. Like the trajectory file, these additional files are needed only for analyzing a simulation's results, but not to continue it.

Lastly, the total energy of all biases or restraints applied to the colvars appears under the NAMD standard output, under the MISC column.

This section summarizes the file formats of various files that Colvars may be reading or writing.

Configuration files are text files that are generally read as input by NAMD, and may be optionally inlined in a NAMD script (see 3.3.1). Starting from version 2017-02-01, changes in newline encodings are handled transparently, i.e. it is possible to typeset a configuration file in Windows (CR-LF newlines) and then use it with Linux or macOS (LF-only newlines).

Formatted state files, although not written manually, follow otherwise the same text format as configuration files. Binary state files can only be read by the Colvars code itself.

For atom selections that cannot be specified only by using internal Colvars keywords, external index files may also be used following the NDX format used in GROMACS:

[ group_1_name ]

i1 i2 i3 i4 ...

... ... iN

[ group_2_name ]

...

where i1 through iN are 1-based indices. Each group name may not contain spaces or tabs: otherwise, a parsing error will be raised.

Multiple index files may be provided to Colvars, each using the keyword indexFile. Two index files may contain groups with the same names, however these must also represent identical atom selections, i.e. the same sequence of indices including order.

Other than with GROMACS, an index group may also be generated from the VMD command-line interface, using the helper function write_index_group provided in the colvartools folder:

source colvartools/write_index_group.tcl

set sel [atomselect top "resname XXX and not hydrogen"]

write_index_group indexfile.ndx $sel "Ligand"

XYZ coordinate files are text files with the extension “.xyz". They are read by the Colvars module using an internal reader, and expect the following format:

| Comment | line | ||

| … | |||

where is the number of atomic coordinates in the file and is the chemical element of the -th atom. Because is not used in Colvars, any string that does not contain tabs or spaces is acceptable.

Note: all XYZ coordinates are assumed to be expressed in Å units.

An XYZ file may contain either one of the following scenarios:

- The file contains as many coordinates as the atoms that they are being read for: all coordinates will be read from the file following the same order as the atoms appear in the selection generated using the keywords listed in section 5. (Note that the order is guaranteed only if a single type of selection keyword is used one or more times, and not guaranteed when different types of selection keywords are used.)

- The file contains more coordinates than needed, and it is assumed to contain coordinates for the entire system: only coordinates that match the numeric indices of the selected atoms are read, in order of increasing number.

XYZ-file coordinates are read directly by Colvars and stored internally as double-precision floating point numbers.

PDB coordinate files are read by the Colvars module using existing functionality in NAMD, and therefore follow the same format. The values of the atomic coordinates and other fields, such as occupancy or temperature factors, are then communicated to Colvars by NAMD.

PDB files may be used either as one of the available mechanisms to select atoms (see the atomsFile keyword), or more frequently to read reference coordinates for least-squares fit alignment (see the refPositionsFile keyword).

To select atoms via the atomsFile keyword, the option atomsFile is required, and atoms are selected based on either one of the following cases.

- All atoms with a non-zero value of the corresponding column are selected.

- If and only if atomsColValue is provided, only atoms with a value of atomsCol equaling atomsColValue are selected. This can be useful to reuse the same PDB file for generating multiple selections.

To read coordinates via the refPositionsFile keyword, there are four possible scenarios.

- The file contains as many coordinates as the atoms that they are being read for: all coordinates will be read from the file following the same order as the atoms appear in the selection generated using the keywords listed in section 5. (Note that the order is guaranteed only if a single type of selection keyword is used one or more times, and not guaranteed when different types of selection keywords are used.)

- The file contains more coordinates than needed, and it is assumed to contain coordinates for the entire system: only coordinates that match the numeric indices of the selected atoms are read, in order of increasing number.

- If the corresponding refPositionsCol keyword is specified, only positions with a non-zero value of the column refPositionsCol are read. This is particularly useful when all atoms were selected via atomsFile and atomsCol, which can then be the same as refPositionsCol for loading coordinates.

- This is a special case of the previous point: if both refPositionsCol and refPositionsColValue are specified, only atoms for which the refPositionsCol column as the value refPositionsColValue are read.

Due to the fixed-precision PDB format, it is not recommended to use PDB files to read coordinates when precision is a concern, and the XYZ format (see 3.8.2) is recommended instead.

Many simulation methods and analysis tools write files that contain functions of the collective variables tabulated on a grid (e.g. potentials of mean force or multidimensional histograms) for the purpose of analyzing results. Such files are produced by ABF (6.2), metadynamics (6.5), multidimensional histograms (6.11), as well as any restraint with optional thermodynamic integration support (6.1).

In some cases, these files may also be read as input of a new simulation. Suitable input files for

this purpose are typically generated as output files of previous simulations, or directly by

the user in the specific case of ensemble-biased metadynamics (6.5.5). This section

explains the “multicolumn" format used by these files. For a multidimensional function

,

,

… the

multicolumn grid format is defined as follows:

| # | ||||||

| # | ||||||

| # | ||||||

| # | … | … | … | … | ||

| # | ||||||

| … | f(, , …, ) | |||||

| … | f(, , …, ) | |||||

| … | … | … | … | … | ||

Lines beginning with the character “#" are the header of the file. is the number of collective variables sampled by the grid. For each variable , is the lowest value sampled by the grid (i.e. the left-most boundary of the grid along ), is the width of each grid step along , is the number of points and is a flag whose value is 1 or 0 depending on whether the grid is periodic along . In most situations:

- is given by the lowerBoundary keyword of the variable ;

- is given by the width keyword;

- is calculated from the two above numbers and the upperBoundary keyword;

- is set to 1 if and only if is periodic and the grids' boundaries cover its period.

How the grid's boundaries affect the sequence of points depends on how the contents of the file were computed. In many cases, such as histograms and PMFs computed by metadynamics (6.5.5), the values of in the first few columns correspond to the midpoints of the corresponding bins, i.e. . However, there is a slightly different format in PMF files computed by ABF (6.2) or other biases that use thermodynamic integration (6.1). In these cases, it is free-energy gradients that are accumulated on an (npoints)-long grid along each variable : after these gradients are integrated, the resulting PMF is discretized on a slightly larger grid with (npoints+1) points along (unless the interval is periodic). Therefore, the grid's outer edges extend by above and below the specified boundaries, so that for instance in the header appears to be shifted back by compared to what would be expected. Please keep this difference in mind when comparing PMFs computed by different methods.

After the header, the rest of the file contains values of the tabulated function

,

,

…, one for each line.

The first columns

contain values of ,

,

… and the last column contains

the value of the function .

Points are sorted in ascending order with the fastest-changing values at the right (“C-style" order). Each sweep of the

right-most variable

is terminated by an empty line. For two dimensional grid files, this allows quick visualization by programs

such as GNUplot.

Example 1: multicolumn text file for a one-dimensional histogram with lowerBoundary = 15, upperBoundary = 48 and width = 0.1.

| # | 1 | ||||

| # | 15 | 0.1 | 330 | 0 | |

| 15.05 | 6.14012e-07 | ||||

| 15.15 | 7.47644e-07 | ||||

| … | … | ||||

| 47.85 | 1.65944e-06 | ||||

| 47.95 | 1.46712e-06 | ||||

Example 2: multicolumn text file for a two-dimensional histogram of two dihedral angles (periodic interval with 6 bins):

| # | 2 | ||||

| # | -180.0 | 6.0 | 30 | 1 | |

| # | -180.0 | 6.0 | 30 | 1 | |

| -177.0 | -177.0 | 8.97117e-06 | |||

| -177.0 | -171.0 | 1.53525e-06 | |||

| … | … | … | |||

| -177.0 | 177.0 | 2.442956-06 | |||

| -171.0 | -177.0 | 2.04702e-05 | |||

| … | … | … | |||

The Colvars trajectory file (with a suffix .colvars.traj) is a plain text file (scientific notation with 14-digit precision) whose columns represent quantities such as colvar values, applied forces, or individual restraints' energies. Under most scenarios, plotting or analyzing this file is straightforward: for example, the following contains a variable “" and the energy of a restraint “":

# step A E_rA

0 1.42467449615693e+01 6.30982865292123e+02

100 1.42282559728026e+01 6.20640585041317e+02

…

Occasionally, if the Colvars configuration is changed mid-run certain quantities may be added or removed, changing the column layout. Labels in comment lines can assist in such cases: for example, consider the trajectory above with the addition of a second variable, “", after 10,000 steps:

# step A E_rA

0 1.42467449615693e+01 6.30982865292123e+02

100 1.42282559728026e+01 6.20640585041317e+02

…

# step A B E_rA

10000 1.38136915830229e+01 9.99574098859265e-01 4.11184644791030e+02

10100 1.36437184346326e+01 9.99574091957314e-01 3.37726286543895e+02

Analyzing the above file with standard tools is possible, but laborious: a convenience script is provided for this and related purposes. It may be used either as a command-line tool or as a Python module:

>>> from plot_colvars_traj import Colvars_traj

>>> traj = Colvars_traj('test.colvars.traj')

>>> print(traj['A'].steps, traj['A'].values)

[ 0 100 ... 10000 10100] [14.246745 14.228256 ... 13.813692 13.643718]

>>> print(traj['B'].steps, traj['B'].values)

[10000 10100] [0.999574 0.9995741]

A collective variable is defined by the keyword colvar followed by its configuration options contained within curly braces:

colvar {

name xi

other options

function_name {

parameters

atom selection

}

}

There are multiple ways of defining a variable:

- The simplest and most common way way is using one of the precompiled functions (here called “components"), which are listed in section 4.1. For example, using the keyword rmsd (section 4.6.1) defines the variable as the root mean squared deviation (RMSD) of the selected atoms.

- A new variable may also be constructed as a linear or polynomial combination of the components listed in section 4.1 (see 4.17 for details).

- A user-defined mathematical function of the existing components (see list in section 4.1), or of the atomic coordinates directly (see the cartesian keyword in 4.9.1). The function is defined through the keyword customFunction (see 4.18 for details).

- A user-defined Tcl function of the existing components (see list in section 4.1), or of the atomic coordinates directly (see the cartesian keyword in 4.9.1). The function is provided by a separate Tcl script, and referenced through the keyword scriptedFunction (see 4.19 for details).

Choosing a component (function) is the only parameter strictly required to define a collective variable. It is also highly recommended to specify a name for the variable:

- name — Name of this colvar

Default: “colvar" + numeric id string, context: colvar

The name is an unique case-sensitive string which allows the Colvars module to identify this colvar unambiguously; it is also used in the trajectory file to label to the columns corresponding to this colvar.

In this context, the function that computes a colvar is called a component. A component's choice and definition consists of including in the variable's configuration a keyword indicating the type of function (e.g. rmsd), followed by a definition block specifying the atoms involved (see 5) and any additional parameters (cutoffs, “reference" values, …). At least one component must be chosen to define a variable: if none of the keywords listed below is found, an error is raised.

The following components implement functions with a scalar value (i.e. a real number):

- distance: distance between two groups;

- distanceZ: projection of a distance vector on an axis;

- distanceXY: projection of a distance vector on a plane;

- distanceInv: mean distance between two groups of atoms (e.g. NOE-based distance);

- angle: angle between three groups;

- dihedral: torsional (dihedral) angle between four groups;

- dipoleAngle: angle between two groups and dipole of a third group;

- dipoleMagnitude: magnitude of the dipole of a group of atoms;

- polarTheta: polar angle of a group in spherical coordinates;

- polarPhi: azimuthal angle of a group in spherical coordinates;

- eulerPhi: Roll angle of rotation from references coordinates;

- eulerTheta: Pitch angle of rotation from references coordinates;

- eulerPsi: Yaw angle of rotation from references coordinates;

- coordNum: coordination number between two groups;

- selfCoordNum: coordination number of atoms within a group;

- hBond: hydrogen bond between two atoms;

- rmsd: root mean square deviation (RMSD) from a set of reference coordinates;

- eigenvector: projection of the atomic coordinates on a vector;

- mapTotal: total value of a volumetric map;

- orientationAngle: angle of the best-fit rotation from a set of reference coordinates;

- orientationProj: cosine of orientationProj;

- spinAngle: projection orthogonal to an axis of the best-fit rotation from a set of reference coordinates;

- tilt: projection on an axis of the best-fit rotation from a set of reference coordinates;

- gyration: radius of gyration of a group of atoms;

- inertia: moment of inertia of a group of atoms;

- inertiaZ: moment of inertia of a group of atoms around a chosen axis;

- alpha: -helix content of a protein segment.

- dihedralPC: projection of protein backbone dihedrals onto a dihedral principal component.

Some components do not return scalar, but vector values:

- distanceVec: distance vector between two groups (length: 3);

- distanceDir: unit vector parallel to distanceVec (length: 3);

- cartesian: vector of atomic Cartesian coordinates (length: times the number of Cartesian components requested, X, Y or Z);

- distancePairs: vector of mutual distances (length: );

- orientation: best-fit rotation, expressed as a unit quaternion (length: 4).

The types of components used in a colvar (scalar or not) determine the properties of that colvar, and particularly which biasing or analysis methods can be applied.

What if “X" is not listed? If a function type is not available on this list, it may be possible to define it as a polynomial superposition of existing ones (see 4.17), a custom function (see 4.18), or a scripted function (see 4.19).

In the rest of this section, all available component types are listed, along with their physical units and their ranges of values, if limited. Such ranges are often used to define automatically default sampling intervals, for example by setting the parameters lowerBoundary and upperBoundary in the parent colvar.

For each type of component, the available configurations keywords are listed: when two components share certain keywords, the second component references to the documentation of the first one that uses that keyword. The very few keywords that are available for all types of components are listed in a separate section 4.14.

In all colvar components described below, the following rules apply concerning periodic boundary conditions (PBCs):

- Distance vectors between two coordinates , are calculated following the minimum-image convention by default, unless forceNoPBC is enabled. ( and may be either individual atomic coordinates, or centers of mass of two groups.)

- For all other functions of individual atomic coordinates, , it is assumed that all atoms that are part of the same group are in the same periodic unit cell (see 5.3).

- forceNoPBC — Use absolute rather than minimum-image distances?

Default: no boolean, context: any component

If this keyword is set to yes, PBCs will be ignored when calculating this component. This is only useful in a limited number of special cases, e.g. to describe the distance between remote points of a single macromolecule, which cannot be split across periodic cell boundaries, and for which the minimum-image distance might give the wrong result because of a relatively small periodic cell.

The distance {...} block defines a distance component between the two atom groups, group1 and group2.

List of keywords (see also 4.2, 4.14, 4.15 and 4.17 for additional options):

- group1 — First group of atoms

Atom group, context: distance

First group of atoms. - group2 — analogous to group1

- oneSiteTotalForce — Measure total force on group 1 only?

Default: no boolean, context: angle, dipoleAngle, dihedral

If this is set to yes, the total force is measured along a vector field (see equation (28) in section 6.2) that only involves atoms of group1. This option is only useful for ABF, or custom biases that compute total forces. See section 6.2 for details. - forceNoPBC — Use absolute rather than minimum-image distances? (see description)

Default: no

The value returned is a positive number (in Å), ranging from to the largest possible interatomic distance within the chosen boundary conditions (with PBCs, the minimum image convention is used unless the forceNoPBC option is set).

The distanceZ {...} block defines a distance projection component, which can be seen as measuring the distance between two groups projected onto an axis, or the position of a group along such an axis. The axis can be defined using either one reference group and a constant vector, or dynamically based on two reference groups. One of the groups can be set to a dummy atom to allow the use of an absolute Cartesian coordinate.

List of keywords (see also 4.2, 4.14, 4.15 and 4.17 for additional options):

- main — Main group of atoms

Atom group, context: distanceZ

Group of atoms whose position is measured. - ref — Reference group of atoms

Atom group, context: distanceZ

Reference group of atoms. The position of its center of mass is noted below. - ref2 — Secondary reference group

Default: none Atom group, context: distanceZ

Optional group of reference atoms, whose position can be used to define a dynamic projection axis: . In this case, the origin is , and the value of the component is . - axis — Projection axis

Default: (0.0, 0.0, 1.0) (x, y, z) triplet, context: distanceZ

This vector will be normalized to define a projection axis for the distance vector joining the centers of groups ref and main. The value of the component is then . The vector should be written as three components separated by commas and enclosed in parentheses. - oneSiteTotalForce — same definition as oneSiteTotalForce (distance component)

- forceNoPBC — Use absolute rather than minimum-image distances? (see description)

Default: no

This component returns a number (in Å) whose range is determined by the chosen boundary conditions. For instance, if the axis is used in a simulation with periodic boundaries, the returned value ranges between and , where is the box length along (this behavior is disabled if forceNoPBC is set).

The distanceXY {...} block defines a distance projected on a plane, and accepts the same keywords as the component distanceZ, i.e. main, ref, either ref2 or axis, and oneSiteTotalForce. It returns the norm of the projection of the distance vector between main and ref onto the plane orthogonal to the axis. The axis is defined using the axis parameter or as the vector joining ref and ref2 (see distanceZ above).

List of keywords (see also 4.2, 4.14, 4.15 and 4.17 for additional options):

- main — same definition as main (distanceZ component)

- ref — same definition as ref (distanceZ component)

- ref2 — same definition as ref2 (distanceZ component)

- axis — same definition as axis (distanceZ component)

- oneSiteTotalForce — same definition as oneSiteTotalForce (distance component)

- forceNoPBC — Use absolute rather than minimum-image distances? (see description)

Default: no

The distanceVec component computes the 3-dimensional vector joining the centers of mass of group1 and group2. Its values are therefore multi-dimensional and are subject to the restrictions listed in 4.16. Moreover, when computing differences between two different values of a distanceVec variable the minimum-image convention is assumed (unless forceNoPBC is enabled).

List of keywords (see also 4.2, 4.14, 4.15 and 4.17 for additional options):

- group1 — same definition as group1 (distance component)

- group2 — analogous to group1

- oneSiteTotalForce — same definition as oneSiteTotalForce (distance component)

- forceNoPBC — Use absolute rather than minimum-image distances? (see description)

Default: no

The distanceDir {...} block defines a distance unit vector component, which accepts the same keywords as the component distance: group1, group2, and forceNoPBC. It returns a 3-dimensional unit vector , with .

This multi-dimensional variable has two intrinsic degrees of freedom: however, these cannot be sampled independently as one-dimensional variables. A decomposition in two dimensions can be done using polarTheta and polarPhi angles, with the caveat that the latter is ill-defined when the former approaches 0 or 180.

The distance between two values of distanceDir is calculated internally as the angle (in radians) between the two unit vectors: this definition adapts the standard Euclidean distance to the unit sphere, to ensure that restraint forces comply with the mathematical constraint.

List of keywords (see also 4.2, 4.14, 4.15 and 4.17 for additional options):

- group1 — same definition as group1 (distance component)

- group2 — analogous to group1

- oneSiteTotalForce — same definition as oneSiteTotalForce (distance component)

- forceNoPBC — Use absolute rather than minimum-image distances? (see description)

Default: no

The distanceInv {...} block defines a generalized mean distance between two groups of atoms 1 and 2, where each distance is taken to the power :

| (2) |

where is the distance between atoms and in groups 1 and 2 respectively, and is an even integer.

List of keywords (see also 4.2, 4.14, 4.15 and 4.17 for additional options):

- group1 — same definition as group1 (distance component)

- group2 — analogous to group1

- oneSiteTotalForce — same definition as oneSiteTotalForce (distance component)

- exponent — Exponent

in equation 2

Default: 6 positive even integer, context: distanceInv

Defines the exponent to which the individual distances are elevated before averaging. The default value of 6 is useful for example to applying restraints based on NOE-measured distances. - forceNoPBC — Use absolute rather than minimum-image distances? (see description)

Default: no

This component returns a number ranging from to the largest possible distance within the chosen boundary conditions.

The angle {...} block defines an angle, and contains the three blocks group1, group2 and group3, defining the three groups. It returns an angle (in degrees) within the interval .

List of keywords (see also 4.2, 4.14, 4.15 and 4.17 for additional options):

- group1 — same definition as group1 (distance component)

- group2 — analogous to group1

- group3 — analogous to group1

- oneSiteTotalForce — same definition as oneSiteTotalForce (distance component)

- forceNoPBC — Use absolute rather than minimum-image distances? (see description)

Default: no

The dipoleAngle {...} block defines an angle, and contains the three blocks group1, group2 and group3, defining the three groups, being group1 the group where dipole is calculated. It returns an angle (in degrees) within the interval .

List of keywords (see also 4.2, 4.14, 4.15 and 4.17 for additional options):

- group1 — same definition as group1 (distance component)

- group2 — analogous to group1

- group3 — analogous to group1

- oneSiteTotalForce — same definition as oneSiteTotalForce (distance component)

- forceNoPBC — Use absolute rather than minimum-image distances? (see description)

Default: no

The dihedral {...} block defines a torsional angle, and contains the blocks group1, group2, group3 and group4, defining the four groups. It returns an angle (in degrees) within the interval . The Colvars module calculates all the distances between two angles taking into account periodicity. For instance, reference values for restraints or range boundaries can be defined by using any real number of choice.

List of keywords (see also 4.2, 4.14, 4.15 and 4.17 for additional options):

- group1 — same definition as group1 (distance component)

- group2 — analogous to group1

- group3 — analogous to group1

- group4 — analogous to group1

- oneSiteTotalForce — same definition as oneSiteTotalForce (distance component)

- forceNoPBC — Use absolute rather than minimum-image distances? (see description)

Default: no

The polarTheta {...} block defines the polar angle in spherical coordinates, for the center of mass of a group of atoms described by the block atoms. It returns an angle (in degrees) within the interval . To obtain spherical coordinates in a frame of reference tied to another group of atoms, use the fittingGroup (5.2) option within the atoms block. An example is provided in file examples/11_polar_angles.in of the Colvars public repository.

List of keywords (see also 4.2, 4.14, 4.15 and 4.17 for additional options):

- atoms — Group of atoms defining this function

Atom group, context: polarPhi

Defines the group of atoms for the COM of which the angle should be calculated. - forceNoPBC — Use absolute rather than minimum-image distances? (see description)

Default: no

The polarPhi {...} block defines the azimuthal angle in spherical coordinates, for the center of mass of a group of atoms described by the block atoms. It returns an angle (in degrees) within the interval . The Colvars module calculates all the distances between two angles taking into account periodicity. For instance, reference values for restraints or range boundaries can be defined by using any real number of choice. To obtain spherical coordinates in a frame of reference tied to another group of atoms, use the fittingGroup (5.2) option within the atoms block. An example is provided in file examples/11_polar_angles.in of the Colvars public repository.

List of keywords (see also 4.2, 4.14, 4.15 and 4.17 for additional options):

- atoms — Group of atoms defining this function

Atom group, context: polarPhi

Defines the group of atoms for the COM of which the angle should be calculated. - forceNoPBC — Use absolute rather than minimum-image distances? (see description)

Default: no

Note: polarPhi is ill-defined when the corresponding polarTheta component is close to 0 or 180; please take measures to avoid sampling these configurations in your simulations.

The coordNum {...} block defines a coordination number (or number of contacts), which calculates the function , where is the “cutoff" distance, and and are exponents that can control its long range behavior and stiffness [3]. This function is summed over all pairs of atoms in group1 and group2:

| (3) |

List of keywords (see also 4.2, 4.14, 4.15 and 4.17 for additional options):

- group1 — same definition as group1 (distance component)

- group2 — analogous to group1

- cutoff — “Interaction" distance (Å)

Default: 4.0 Å positive decimal, context: coordNum

This number defines the switching distance to define an interatomic contact: for , the switching function is close to 1, at it has a value of ( with the default and ), and at it goes to zero approximately like . Hence, for a proper behavior, must be larger than . - cutoff3 — Reference distance vector (Å)

Default: (4.0, 4.0, 4.0) Å “(x, y, z)" triplet of positive decimals, context: coordNum

The three components of this vector define three different cutoffs for each direction. This option is mutually exclusive with cutoff. - expNumer — Numerator exponent

Default: 6 positive even integer, context: coordNum

This number defines the exponent for the switching function. - expDenom — Denominator exponent

Default: 12 positive even integer, context: coordNum

This number defines the exponent for the switching function. - group2CenterOnly — Use only group2's center of mass

Default: off boolean, context: coordNum

If this option is on, only contacts between each atoms in group1 and the center of mass of group2 are calculated (by default, the sum extends over all pairs of atoms in group1 and group2). If group2 is a dummyAtom, this option is set to yes by default. - tolerance — Pairlist control

Default: 0.0 decimal, context: coordNum

This controls the pair list feature, dictating the minimum value for each summation element in Eq. 3 such that the pair that contributed the summation element is included in subsequent simulation timesteps until the next pai r list recalculation. For most applications, this value should be small (eg. 0.001) to avoid missing important contributions to the overall sum. Higher values will improve performance by reducing the number of pairs that contribute to the sum. Values above 1 will exclude all possible pair interactions. Similarly, values below 0 will never exclude a pair from consideration. To ensure continuous forces, Eq. 3 is further modified by subtracting the tolerance and then rescaling so that each pair covers the range . - pairListFrequency — Pairlist regeneration frequency

Default: 100 positive integer, context: coordNum

This controls the pairlist feature, dictating how many steps are taken between regenerating pair lists if the tolerance is greater than 0. - forceNoPBC — Use absolute rather than minimum-image distances? (see description)

Default: no

This component returns a dimensionless number, which ranges from approximately 0 (all interatomic distances are much larger than the cutoff) to (all distances are less than the cutoff), or if group2CenterOnly is used. For performance reasons, at least one of group1 and group2 should be of limited size or group2CenterOnly should be used: the cost of the loop over all pairs grows as . Setting ameliorates this to some degree, although every pair is still checked to regenerate the pair list.

The selfCoordNum {...} block defines a coordination number similarly to the component coordNum, but the function is summed over atom pairs within group1:

| (4) |

The keywords accepted by selfCoordNum are a subset of those accepted by coordNum, namely group1 (here defining all of the atoms to be considered), cutoff, expNumer, and expDenom.

List of keywords (see also 4.2, 4.14, 4.15 and 4.17 for additional options):

- group1 — same definition as group1 (coordNum component)

- cutoff — same definition as cutoff (coordNum component)

- cutoff3 — same definition as cutoff3 (coordNum component)

- expNumer — same definition as expNumer (coordNum component)

- expDenom — same definition as expDenom (coordNum component)

- tolerance — same definition as tolerance (coordNum component)

- pairListFrequency — same definition as pairListFrequency (coordNum component)

- forceNoPBC — Use absolute rather than minimum-image distances? (see description)

Default: no

This component returns a dimensionless number, which ranges from approximately 0 (all interatomic distances much larger than the cutoff) to (all distances within the cutoff). For performance reasons, group1 should be of limited size, because the cost of the loop over all pairs grows as .

The hBond {...} block defines a hydrogen bond, implemented as a coordination number (eq. 3) between the donor and the acceptor atoms. Therefore, it accepts the same options cutoff (with a different default value of 3.3 Å), expNumer (with a default value of 6) and expDenom (with a default value of 8). Unlike coordNum, it requires two atom numbers, acceptor and donor, to be defined. It returns a dimensionless number, with values between 0 (acceptor and donor far outside the cutoff distance) and 1 (acceptor and donor much closer than the cutoff).

List of keywords (see also 4.2, 4.14, 4.15 and 4.17 for additional options):

- acceptor — Number of the acceptor atom

positive integer, context: hBond

Number that uses the same convention as atomNumbers. - donor — analogous to acceptor

- cutoff — same definition as cutoff (coordNum component)

Note: default value is 3.3 Å. - expNumer — same definition as expNumer (coordNum component)

Note: default value is 6. - expDenom — same definition as expDenom (coordNum component)

Note: default value is 8. - forceNoPBC — Use absolute rather than minimum-image distances? (see description)

Default: no

The block rmsd {...} defines the root mean square replacement (RMSD) of a group of atoms with respect to a reference structure. For each set of coordinates , the colvar component rmsd calculates the optimal rotation that best superimposes the coordinates onto a set of reference coordinates . Both the current and the reference coordinates are centered on their centers of geometry, and . The root mean square displacement is then defined as:

| (5) |

The optimal rotation is calculated within the formalism developed in reference [4], which guarantees a continuous dependence of with respect to .

List of keywords (see also 4.2, 4.14, 4.15 and 4.17 for additional options):

- atoms — Group of atoms defining this function

Atom group, context: rmsd

Defines the group of atoms of which the RMSD should be calculated. Optimal fit options (such as refPositions and rotateToReference) should typically NOT be set within this block. Exceptions to this rule are the special cases discussed in the Advanced usage paragraph below. - refPositions — Reference coordinates

space-separated list of (x, y, z) triplets, context: rmsd

This option (mutually exclusive with refPositionsFile) sets the reference coordinates for RMSD calculation, and uses these to compute the roto-translational fit. See the equivalent option refPositions within the atom group definition for details on acceptable formats and other features. - refPositionsFile — Reference coordinates file

UNIX filename, context: rmsd

This option (mutually exclusive with refPositions) sets the reference coordinates for RMSD calculation, and uses these to compute the roto-translational fit. See the equivalent option refPositionsFile within the atom group definition for details on acceptable file formats and other features. - refPositionsCol — PDB column containing atom flags

O, B, X, Y, or Z, context: rmsd

If refPositionsFile is a PDB file that contains all the atoms in the topology, this option may be provided to set which PDB field is used to flag the reference coordinates for atoms. - refPositionsColValue — Atom selection flag in the PDB column

positive decimal, context: rmsd

If defined, this value identifies in the PDB column refPositionsCol of the file refPositionsFile which atom positions are to be read. Otherwise, all positions with a non-zero value are read. - atomPermutation — Alternate ordering of atoms for RMSD computation

List of atom numbers, context: rmsd

If defined, this parameter defines a re-ordering (permutation) of the 1-based atom numbers that can be used to compute the RMSD, typically due to molecular symmetry. This parameter can be specified multiple times, each one defining a new permutation: the returned RMSD value is the minimum over the set of permutations. For example, if the atoms making up the group are 6, 7, 8, 9, and atoms 7, 8, and 9 are invariant by circular permutation (as the hydrogens in a CH3 group), a symmetry-adapted RMSD would be obtained by adding:

atomPermutation 6 8 9 7

atomPermutation 6 9 7 8

This will result in these 2 atom orders being considered in addition to the order used when defining the atom group. Note that this does not affect the least-squares roto-translational fit. Therefore, this feature is mostly useful when using custom fitting parameters within the atom group, such as fittingGroup, or when fitting is disabled altogether. For details, see reference [5]. - forceNoPBC — Use absolute rather than minimum-image distances? (see description)

Default: no

This component returns a positive real number (in Å).

In the standard usage as described above, the rmsd component calculates a minimum RMSD, that is, current coordinates are optimally fitted onto the same reference coordinates that are used to compute the RMSD value. The fit itself is handled by the atom group object, whose parameters are automatically set by the rmsd component. For very specific applications, however, it may be useful to control the fitting process separately from the definition of the reference coordinates, to evaluate various types of non-minimal RMSD values. This can be achieved by setting the related options (refPositions, etc.) explicitly in the atom group block. This allows for the following non-standard cases:

- applying the optimal translation, but no rotation (rotateToReference off), to bias or restrain the shape and orientation, but not the position of the atom group;

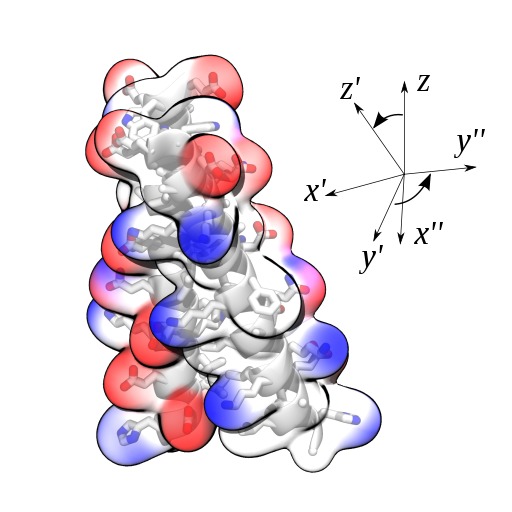

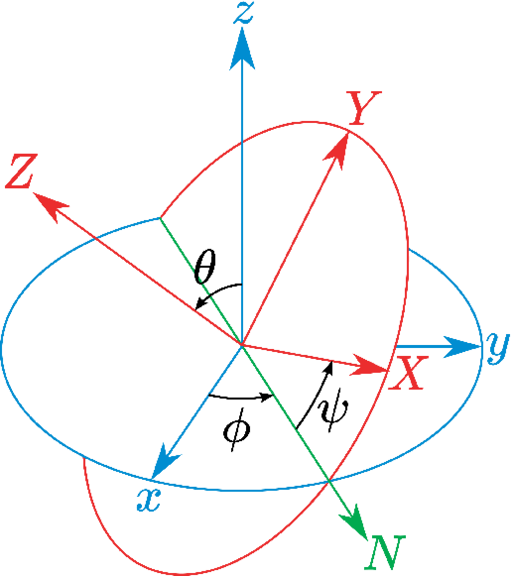

- applying the optimal rotation, but no translation (centerToReference off), to bias or restrain the shape and position, but not the orientation of the atom group;